A

common misconception among feminists and those curious about feminist thought

is that women need to stop criticizing other women. Taking it further, some

people believe feminists must not criticize other feminists. Sheryl Sandberg

talks about the shortness of Marissa Mayer’s maternity leave and the criticism

that followed her announcement in her new book, “Lean In.” I agree with her

that Mayer has been labeled “the CEO that represents all working mothers,” and

that is unfair. I think some of the criticism of Mayer’s maternity leave, her

personal choice, is undeserved. But I disagree with her assertion that women

need to stop criticizing each other, especially feminists who criticize other

feminists.

Political

and social movements need introspection. There are plenty of groups that could

benefit from a little introspection. The Republican Party is a great example.

Feminists may agree on some of the main problems that need to be addressed,

such as pay equity, maternity leave, and rape culture, but feminists differ on

what solutions are best. Some feminists are “choice” feminists who believe all

choices women make should be celebrated and others believe that the reasons

behind those choices are still relevant and influenced by traditional gender

roles, as Sandberg does.

Sandberg

laments the fact that Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem did not get along, to

say the least. Friedan considered some of Steinem’s statements about marriage

and relationships with men too extreme. In the book “Interviews with Betty

Friedan,” edited by Janann Sherman, Friedan said of her feud with Steinem:

“They

can’t seem to understand that every important movement is going to have a

certain amount of fighting over turf. Men do it all the time in politics…When

she said marriage was a form of prostitution, I spoke up and criticized her.

Her view had nothing to do with my kind of feminism and I said so…That extreme

kind of thinking tends to come from women who hate having to deal with the

complexities of juggling a career and a family and so, almost literally, they

want to throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

What

Sandberg fails to realize is how these disagreements between feminists of

different eras helped grow the feminist movement. Steinem wanted to bring

feminism in a new, and I would argue a more inclusive and progressive, direction.

For example, “The Feminine Mystique” benefitted many white middle class women

living as housewives, but it didn’t apply to women of a different sociological

background, who always had to work. Their issues were different. Friedan was also

considered hostile to the gay rights movement. In a New York Observer article, Alix Kates Shulman said Friedan called

feminist lesbians the “lavender menace.” In “The Feminine Mystique,” she argued

that housewives who smothered their children with affection could turn their

sons gay through resentment of women, and in the context of her argument, I

doubt this was considered a positive result. Friedan wrote:

“Whether

or not there has been an increase of homosexuality in America, there has

certainly been in recent years an increase in its overt manifestations. I do

not think this is unrelated to the national embrace of the feminine mystique.

For the feminine mystique has glorified and perpetuated in the name of

femininity a passive, childlike immaturity which is passed on from mothers to

sons, as well as daughters. Male

homosexuals—and the male Don Juans, whose compulsion to test their potency is

often caused by unconscious homosexuality—are, no less than the female

sex-seekers, Peter Pans, forever childlike…”

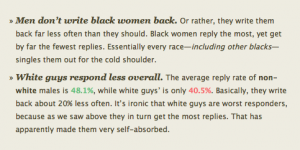

Steinem

also made major inroads to include more feminists of color and allied the

feminist movement with the civil rights movement. The feminist conversation is

still too dominated by white women, especially upper-middle class white women,

but Steinem made progress in that regard. None of this information is meant to

demonize Friedan, who founded The National Organization for Women and the

National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws and fought hard for equal pay,

or celebrate Steinem, who has her share of critics over statements she has made

about transsexuals and the legalization of prostitution. The feminist movement

desperately needed both Friedan and Steinem’s contributions, despite their

disagreements. Without one, there wouldn’t be the other.

We

can’t discourage feminists from arguing with each other. I understand that

Sandberg is concerned with the portrayal of women engaging in perceived

“catfights.” She wants feminists to work together in order to solve major

problems. But feminism’s birthing pains helped it grow into a stronger, more

diverse movement. As Sandberg points out, women have major hurdles to jump

over. Women are still underrepresented in management and held back from

pursuing promotions and engaging in office discussions. If “Lean In” proves anything,

it is that the solutions to these problems will not be easy to find or straightforward.

The issues she describes are nuanced and complicated. These are the kind of

problems that must be solved by a diverse group of people with conflicting

views. We need creative solutions, which we will never hope to find if we brush

over our conflicts or shut out people or who are likely to disagree.